I recently switched from taking the train to taking the bus for my commute home from work. I will always be a fan of the rails. I love everything about them, from the feel of a train ride, to the dedicated space for travel, to generally firm scheduling and the fact that they are independent from other forms of transportation (unless there are grade crossings involved). However, the bus became cheaper (due to to extenuating circumstances, not merely system prices) and here I am taking it!

However, I will never get used to being stuck in traffic during the commute. I find it incredibly frustrating to watch traffic go the same speed as the bus or faster. My transit elitism leads me to believe that I am entitled to go faster than people traveling alone in individual cars. In fact, if more planners thought this way, I am positive more people would be riding public transit, it’s all about marginal costs and returns.

We all know that the bus has a sad history of being disfavored, sometimes used as an instrument of racial and/or class oppression, and generally is perceived as vastly inferior to the personal automobile. However, for all those drivers stuck in endless traffic on metropolitan America’s overcrowded highways, think about how much better life could be if most people took the bus (let alone rode a bike). While I recognize the importance of biking and that more streets, workplaces, and transit stations should accommodate bicycles, it is also relevant that many people due to age, distance, weather, etc. cannot bike to work.

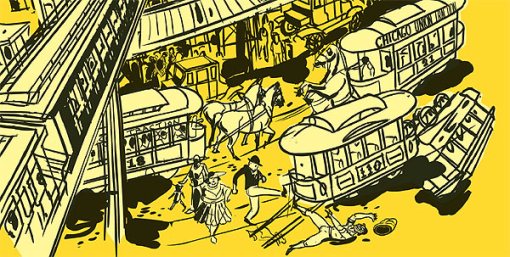

The above image from Transportation Alternatives (a New York advocacy group)–and similar to a more photographically deceptive German image–illustrates the incredible power of public transit. Moving many people from many moving motorized vehicles into one is a huge coup for traffic flow (not to mention safety) and commuter sanity. Even though some companies are trying to solve the problem by building smaller cars–and admittedly bikers are very efficient on smaller vehicles–organizing people into larger systems is not efficient and clean, but creates more usable streets. It is one of the many reasons I applaud New York’s engagement with bus rapid transit.

The next time someone gives you a hard time about the bus, whether it is its speed, its comfort, or its perceived social status, remind that person that if more people rode the bus system, and public transit systems in general, not only would our society feel and be more equal, but those buses would move faster and be better for all people in transit, regardless of their mode.

July 13, 2010

The Transit Death Star

Posted by morangre under Public Transportation, Transportation Commentary | Tags: 42nd Street, Bus Rapid Transit, buses, Grand Central Terminal, Heartland Brewery, New York Port Authority, Port Authority Bus Terminal, Public Transportation |Leave a Comment

For thousands of travelers each day, for both commuters and tourists alike, the New York City Port Authority Bus Terminal serves as a portal to the “city that never sleeps.” By all accounts, this is one of the most bustling public transit hubs in the United States, as it serves over 58 million passengers annually. Simply stepping into the main terminal’s entrance on 8th Ave between 41st and 42nd streets, one wonders how this labyrinth even functions to serve it’s purpose of transporting passengers on buses throughout the Northeast. The answer is barely. For instance, just today, I had to wait 25 minutes from the time our bus returned to Port Authority until the time we alighted from the bus due to a last second gate logistic switch. In talking to other friends, apparently this type of experience is the norm, not the exception unfortunately.

It is no secret that buses are treated as second class citizens in New York City. Simply look to the lack of bus rapid transit lanes, a strategy that has shown time and again to work in South America and Europe. City planners and policy makers have always favored subways or commuter rail lines over bus transit. Nowhere is this more evident than in the comparison between Grand Central Station and the Port Authority Bus Terminal. One is a beacon of architectural reclamation and commercial triumph, the other is a seventh rate architectural structure whose only commercial highlight is that it contains a Heartland Brewery (brewery should be used loosely……) by one of the main entrances. Such an important transportation hub should be seen as an architectural landmark. Other nations seem to understand this, even China. Apparently, we in the US, especially in New York, missed the memo.

If the exterior architecture weren’t bad enough, perhaps one should take a closer look at the circuitous paths leading up to the actual bus gates. It is time for a Grand Central-esque overhaul. And while they are at it, why not let the revised structure rise to the sky with gleaming commercial office space like some of these 2008 proposals. I understand this is a massive capital investment that will probably bankrupt the city and state even further. The city and state probably don’t have a cool $10 billion just lying around these days. We must continue to put relevant infrastructure in place that will finally elevate the bus to its proper place alongside trains in the perception of the city public transit user.