The biggest railroad news in a while occurred yesterday when it was announced that Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway were purchasing BNSF (Burlington Northern Santa Fe). Buffett agreed to purchase the 77.4% of the company that he did not already own for $26 billion.

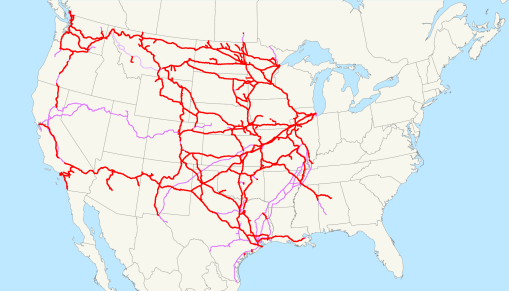

BNSF, which is a relatively new railroad as an entity, is actually a combination of many older railroads including the Burlington Northern and the Santa Fe. The railroad covers 32,000 miles of track, 6,700 locomotives and 220,000 freight cars. The company’s biggest clients are coal and agricultural product shippers.

That begs the question of why Buffett made the investment. Is he betting on trains, coal, industrial agriculture, or all of the above? Streetsblog’s Elana Schor takes a swing at that question:

That environmental rationale for Buffett’s deal struck some in Washington as dubious. Frank O’Donnell, president of the green group Clean Air Watch, wrote on his website that the BNSF deal was “the biggest climate story of the day,” bigger even than the political maneuverings of the Senate environment committee:

This is a $34 billion dollar bet that coal will remain the centerpiece of American energy policy in the future. Buffett clearly believes that coal use will remain strong – and possibly grow. So he is putting his money on a vision of America with no effective climate policy at all – or at least one that doesn’t slow coal growth.

BNSF’s reliance on coal is indisputable; the black stuff has accounted for nearly half of its tonnage this year, and MarketWatch estimates that 10 percent of U.S. electricity comes from coal hauled by the railroad.

As coal-hauling railroads go, however, BNSF has made an attempt to distinguish itself on the energy efficiency end. The railroad is developing an emissions-free hydrogen-powered locomotive, and in May started to test-run a group of GE locomotives that cuts emissions by 40 percent over previous, dirtier models.

My take (and part of Elana’s) is this purchase is a good thing. I personally don’t care if Buffett is invested in coal – because it is admittedly not going anywhere any time soon – because Buffett will be invested in transportation and rail infrastructure. He will be invested in making the rail infrastructure solid, having working trains and hopefully growing the network.

Passenger transportation gets the most news coverage, but freight transportation is equally important. The effect of truck freight transportation on roads and the environment is well documented. Moving more of our freight to rails is good for everyone, including driver safety and those living close to highways.

Moreover, maintaining high quality rail corridors is also good for passenger rail as Amtrak and many public transit commuter rail systems already run on freight-owned rails. Expanding networks is good for the future of commuter and inter-city rail too.

Good for Buffett in seeing that America’s transportation future lies on the tracks, not on its asphalt roads.