**Disclaimer: I am working as an extern in the law department of the Chicago Transit Authority this summer. The CTA does not endorse or sponsor my writing on this blog.**

Being a public transit person creates a lot of conversation, especially with people living in urban centers. Everyone has a public transit story, or complaint, or idea. Transit is the great commonality in cities, not merely as conversation, but as public space and property as well. It is this latter piece, as public property and space that mystifies some people.

At least a handful of people have argued to me that public transit should be privatized or at least support itself financially without any sort of public subsidy. Ironically, these seem to frequently be the same people that are upset that public transit has not made one sort of accommodation or another, whether it is for the handicapped, or enough service, or insufficient cleanliness.

I am in no way against economic efficiency in the sense that transit systems should work to keep costs down. However it is problematic when transit systems are expected to fend for themselves financially (as Governor Christie seems to desire for NJ Transit). Such a system results in a terrible combination of higher fares, less service, and greater inaccessibility for those who least can afford such cutbacks.

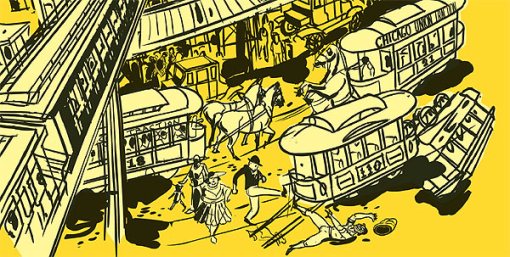

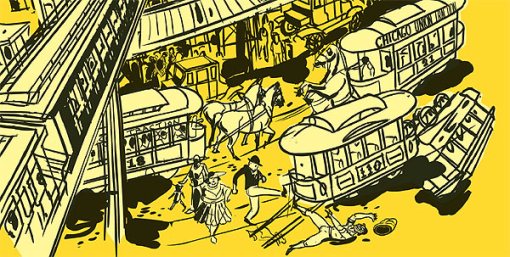

The Chicago Reader recently featured a fantastic history of the early years of the CTA. Robert Loerzel wrote a very-well researched story of how transit systems operated in Chicago from the mid-nineteenth century until the period of public ownership of the urban rails in the mid-twentieth century. Loerzel used this history to illustrate how private ownership of utilities frustrates public purposes. Moreover, especially in this era of governmental criticism, he demonstrates why reformers sought public ownership of utilities, including public transit, in the first place. A great summary quote:

The dream of municipal ownership finally became a reality in 1947, when the Chicago Transit Authority was formed to take over the bankrupt transit lines. Finding enough money to run the CTA has been a problem ever since. “A transit system that was unable to survive on fares as a private enterprise was somehow expected to do so as a public entity in a declining market,” Young wrote. The all-time high for public-transit use in Chicago was the late 1920s, he says, when the city’s streetcars, buses, and trains annually handled more than 1.1 billion rides. In 2009 the CTA handled 521 million rides, not quite half as many.

This history is not unique to Chicago and Loerzel’s article is informative for residents of all cities, not just Chicagoans. Moreover, the lessons regarding transit apply to all public services (e.g. police, health care, roads, energy, water, etc.).

Based on those of my peers who have suggested privatizing transit I think many are just deluded by Reaganomics. The others who believe more sincerely in privatization usually have more sinister anti-urban or racist or classist goals that go along with cutbacks in public transportation.

In these tough financial times it is difficult to find money for all services. However, suggestions to privatize our public transportation systems is not the answer to our woes. Private companies will not put people first, but rather profits. The good of our cities depends on continuing investment (and reasonable expectations of sound fiscal policy with that investment) in our great public properties and spaces, our transportation systems.

For transit lovers and planners across North America, and perhaps around the world, Jane Jacobs — the great opponent of highway builder and ultimate mid-century planner, Robert Moses — has achieved reverential status. I fall into that group; forever grateful that Jane acted to save Greenwich Village, and forever inspired by her insights in the Death and Life of Great American Cities.

For transit lovers and planners across North America, and perhaps around the world, Jane Jacobs — the great opponent of highway builder and ultimate mid-century planner, Robert Moses — has achieved reverential status. I fall into that group; forever grateful that Jane acted to save Greenwich Village, and forever inspired by her insights in the Death and Life of Great American Cities.

April 19, 2010

Does Spirit Airlines Have a Soul?

Posted by meltzerm under Transportation Commentary, Transportation News, Uncategorized | Tags: Airline Market Share, Boston Globe, Carry-on Luggage, Charles Schumer, Checked Luggage, Frank Lautenberg, Jeff Jacoby, Ray LaHood, Spirit Airlines, TSA |1 Comment

I’m not a frequent flyer, but I’ve flown enough to recognize that baggage fees have created a big problem with boarding airplanes. In the era of the checked baggage fee people have chosen to cram everything into a carry-on. Of course, when everyone brings a full-sized carry-on there is not enough room in the overhead bins for all the passenger luggage and the airline inevitably spends a lot of time placing carry-on bags in.

So, to combat that Spirit Airlines has instituted a carry-on bag fee. What has been glossed over is that Spirit is merely providing incentive for passengers to check their bags in the first place rather than carrying them on. The first checked bag will only cost $25 if checked online before arriving at the airport ($20 less than for a potentially smaller carry-on). Therefore Spirit is merely making the carry-on a luxury and giving reason for people to check their luggage. Oh my! Senators are really upset that flights will run more smoothly and that Spirit may actually assist with difficulty of TSA security checks?

Jeff Jacoby of the Boston Globe looks at this issue from a free market perspective.

I agree that politicians have found a pinata not worthy of their attack, especially given that Spirit Airlines has less than 3% of the US market share for airlines.